While the use of fossil fuel driven energy began with the industrial revolution, since then, burning coal to create power has now become a ubiquitous mainstay in the energy sector. The material was first used to generate electricity in the United States around 1880. Undoubtedly, this has led to enormous developments around the world, it does also come with some baggage. In fact, this may be quite the understatement. The rate at which carbon emissions have been released into the atmosphere has grown astronomically in recent decades. In 1950, around six billion tons of CO2 had been emitted globally. By 1990, this figure had almost quadrupled to more than 20 billion tons. Unfortunately, the statistics get considerably worse from there. Each year, we generate over 35 billion tons of CO2. These are truly unimaginable increases from previous years and demonstrate a genuine need for change.

Historically speaking, the rise of fossil fuels was a simple one. The material was far more efficient than any rivalling sources of power. Any concerns would have been far outweighed by the scale of advantages it offered. That was then, however. To assume that over a century later it is still the most viable energy source is a fallacy. This is backed up by numerous statistics. Rocky Mountain Institute is a non-profit organization which was set up in 1982 with a mission to radically improve America’s energy practices. RMI recently conducted a vast body of research, exploring the efficacy of fossil fuels, such was their prevalence. The results were hugely surprising. Almost two-thirds of all primary energy is wasted in energy production, transportation, and use. This amounts to around 400 exajoules, worth over $4.5tn, or almost 5% of global GDP. “Today, most energy is wasted along the way. Out of the 606 EJ of primary energy that entered the global energy system in 2019, some 33% (196 EJ) was lost on the supply side due to energy production and transportation losses before it ever reached a consumer. Another 30% (183 EJ) was lost on the demand side turning final energy into useful energy. That means that of the 606 EJ we put into our energy system per annum, only 227 EJ ended up providing useful energy, like heating a home or moving a truck. That is only 37% efficient overall.” So, this all begs the question, what is driving the continued use of fossil fuels? Given the environmental need, coupled with mounting evidence of much more efficient alternatives, surely it is time to make the switch.

Let’s consider, for a moment, a scenario where the global economy switched to renewable energy overnight. That wouldn’t, however, solve the challenge of carbon currently being pumped into our ecosystems. Scientists at the U.N. believe that billions of tons of carbon need to be removed annually from the atmosphere in order to achieve net zero. In order to remedy this, solutions need to be implemented without delay. Researchers at the University of Oxford have drilled down into ten differed carbon capturing, comparing their value, cost, scalability, and permanence. Looking at methods from industrial and biological, the researchers found that six methods are currently viable and profitable. These range from Biochar and CO2-EOR to forestry and soil carbon sequestration.

“One of the most innovative and exciting tools for battling climate change, however, is direct air carbon capture. This method involves hoovering up carbon directly from the atmosphere before storing it in underground facilities.”

One of the most innovative and exciting tools for battling climate change, however, is direct air carbon capture. This method involves hoovering up carbon directly from the atmosphere before storing it in underground facilities. In an example of its growing influence on the sector, the world’s largest direct air capture plant recently opened in Iceland. The plant, built by Climeworks, has a capacity to capture 36,000 metric tons of CO2 per year, dwarfing the previous record holding plant which is able to capture 4,000 tons. “Starting operations of our Mammoth plant is another proof point in Climeworks’ scale-up journey to megaton capacity by 2030 and gigaton by 2050,” Jan Wurzbacher, co-founder, and co-CEO of Climeworks said.

The Carbon Engineering Direct Air Capture (DAC) carbon capture plant. David Buzzard / Shutterstock.com

The process is an incredible feat of engineering and science. A number of barriers to its widescale adoption exist. While the Icelandic plant will run on the country’s abundant geothermal energy, many other locations do not have this ability. Direct carbon capture requires very high temperatures and is power intensive. While it may seem irrelevant in the face of a climate emergency, the fact is that any potential method for lowering emissions will need to fit in with the budgets of its users. With this in mind, a team at the University of Cambridge set out to develop a low-cost alternative that may assist in direct carbon capture.

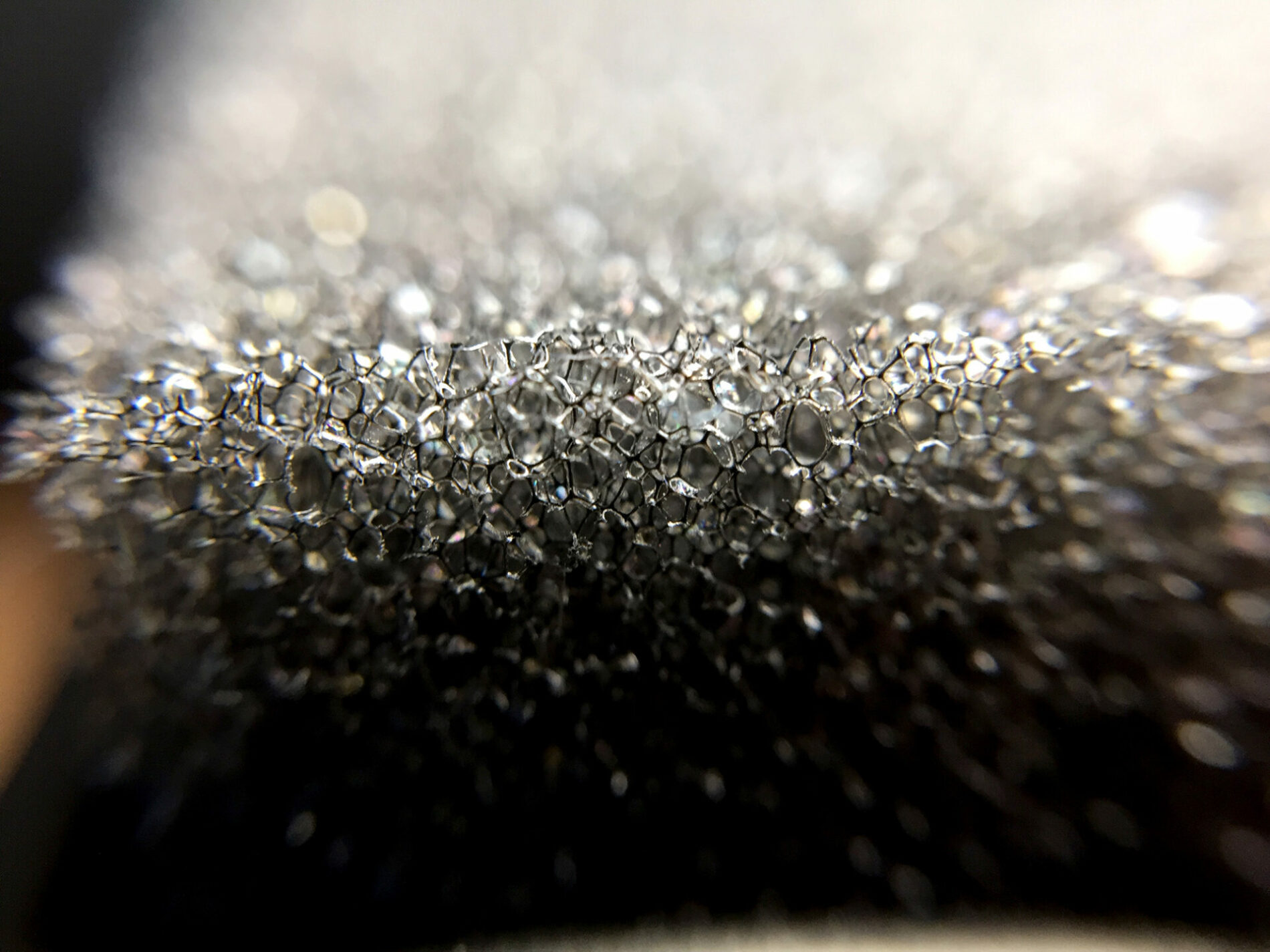

Activated charcoal sponges are porous materials that are most commonly found in household water purifiers. Its purpose in that particular process is to capture chemicals and toxins from water. Most recently, scientists have been investigating the potential for utilizing it in an even more transformative way. While it cannot effectively capture carbon normally, the university team, led by chemist Alexander Forse have discovered that by inserting charged, reactive particles into the charcoal, the resulting material rapidly captures ambient carbon. According to Dr Forse, time is of the essence in terms of investigating the potential for this breakthrough. “Given the scale of the climate emergency, it’s something we need to investigate. The first and most urgent thing we’ve got to do is reduce carbon emissions worldwide. But greenhouse gas removal is also thought to be necessary to achieve net zero emissions and limit the worst effects of climate change. Realistically, we’ve got to do everything we can. This approach opens a door to making all kinds of materials for different applications, in a way that’s simple and energy-efficient.”

As Forse went on to explain, this particular method could be genuinely transformative. Its efficacy is on a par with any other material but more than that, the method is far more sustainable. While direct carbon capture can typically require heat of around 900 degrees Celsius, the team at the University was able to complete the process with temperatures of between 90 and 100 degrees Celsius. “What’s even more promising is this method could be far less energy-intensive, since we don’t require high temperatures to collect the CO2 and regenerate the charcoal sponge.”