The race to reduce and reverse environmental damage is, to use a tired analogy, coming into the home strait. Decisions of vast importance are being made in boardrooms, political offices and homes around the world. However, there is no end in sight to the missed deadlines and start warnings. It seems that no matter what is done, the bar remains unattainably high. It might, therefore, be worth considering the way in which this problem is viewed. As stated above, it is a race. When we drill down, however, we see that this may be a deeply flawed logic. A race implies a winner, a sole entrant that will walk off into the sunset having solved our problems. Evidence is now emerging that, rather than finding a magic bullet, the global community must collaboratively engage to devise a series and collection of methods that will decrease carbon emissions and make restorative changes to the climate. When it comes to finding the most efficient and sustainable practices, it seems that the key is to double up.

As part of the UN Sustainable Development goals, collective action and muti-stakeholder partnerships are a vital component of success. No government or business can successfully solve climate change alone. Interestingly, it seems that the will to collaborate is very much present. A recent report from Baker McKensie shows that 73% of business leaders are willing to collaborate with competitors to achieve net-zero.

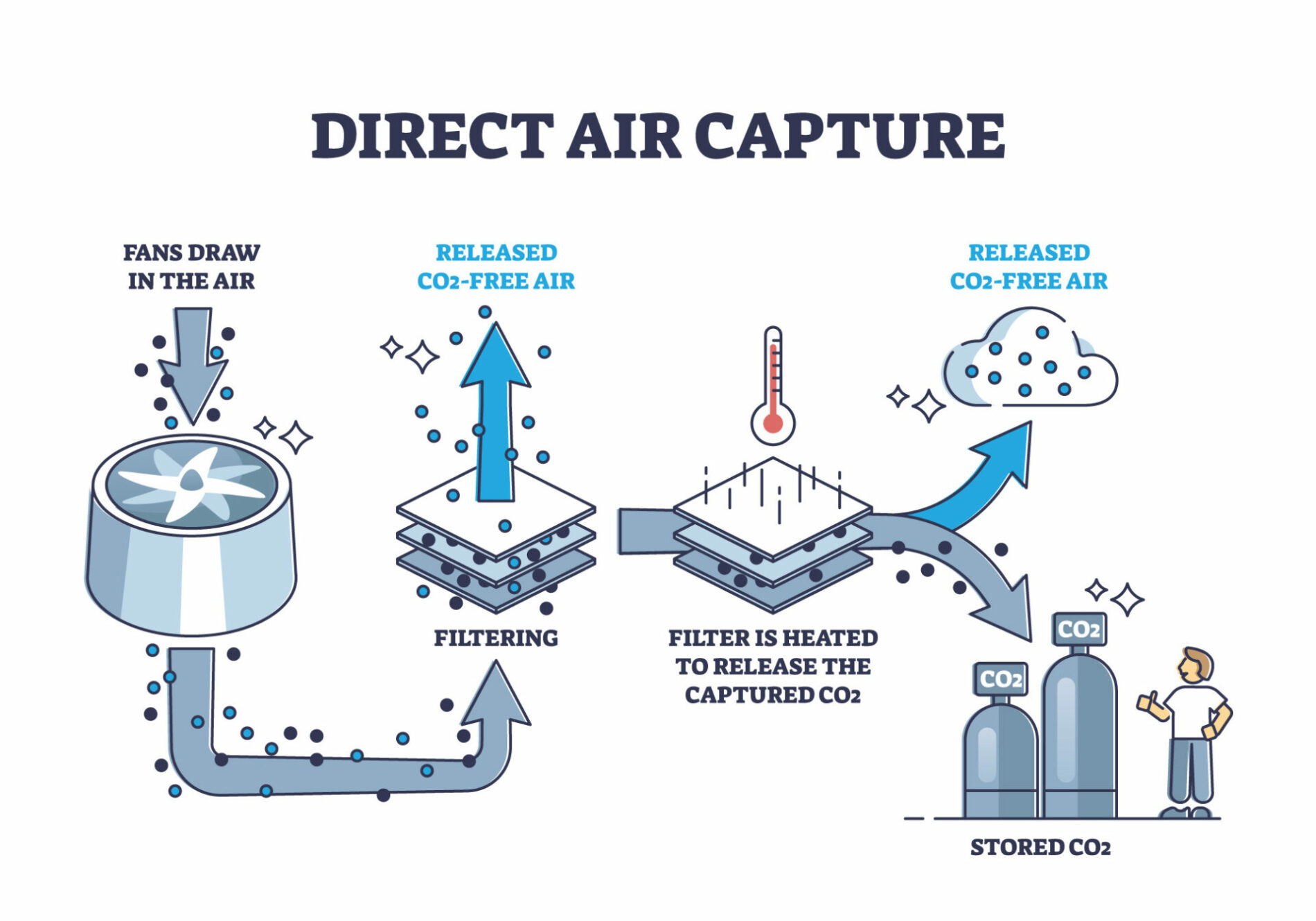

The benefits of collaboration can be seen within the methodologies and tools we use to tackle environmental issues. Efficient energy is clearly a much-needed aspect of the modern world, but its cost can be prohibitive and pivoting to new technologies is time consuming. Reusing materials, or incorporating a second use into their lifecycle, can be an invaluable addition to the process. For example, Direct Air Capture (DAC) technology is the process of removing carbon from the atmosphere and sequestering it underground. While it is an effective way of removing carbon, it has not taken off in the way its inventors had hoped. Until now, the process has been prohibitively expensive in comparison to most other sustainability efforts.

However, a novel process that has been trialed in Ohio State University has discovered a method of combining geothermal energy with DAC technology to produce what is being called a “closed loop.” According to Martina Leveni, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral scholar in civil, environmental and geodetic engineering at The Ohio State University, a combination of innovation led to remarkable results. “Carbon removal technologies are especially helpful in mitigating climate change because we can capture types of emissions that would be hard to cap in other ways. So we thought, could we combine technologies that could be beneficial to one another to meet this goal more efficiently?”

Typically, DAC works by industrial fans blowing air over special chemicals that soak up the carbon but, until now, these fans have been too costly to run. By using cheaper, geothermal energy to power them, the fans could be powered by the very carbon that they are extracting. Not only that, but Leveni and her team explored the use of recycled carbon dioxide into the system to make it even more efficient. The system uses the natural heat found beneath the earth’s surface to continuously produce renewable energy for the DAC system. Speaking about the need for collaboration right across the board, Leveni explained how there is much work that needs to be done. “New technologies can enable one another, and in integrating them, we can tackle climate change. There’s a lot of work to be done to take into account technological readiness and the policies needed to make that research happen.”

It is not just engineers and scientists that need to operate collaboratively, however. The Baker McKensie report went on to say that, more worryingly, not one CEO said they would be willing to accept a 30% loss of revenue to achieve a net-zero transition. It seems that, financially, everyone is waiting for their competitors to act first. This view is echoed at the World Economic Forum where a push is taking place to encourage CEOs to pool their resources, softening the financial impact of any transition.

As CEO of Unilever, Paul Polman set a benchmark of highly sustainable practices and he has carried this knowledge over to a new venture, IMAGINE. Set up in 2019, IMAGINE was founded “with a belief in the positive potential of human beings to lead systemic change.” It works by engaging with industries and sectors to achieve mass buy-in, thereby reaching a tipping point in the industry to ensure a faster transition to sustainable practices. “In the fashion industry, we now have 64 CEOs of the major companies. In food, we work with the 30 biggest companies and CEOs,” said Polman. “What we find is that when the CEOs come together as a collective, they become more courageous.”

IMAGINE was founded “with a belief in the positive potential of human beings to lead systemic change.”

Another example of the positive effects that collaboration can have is Partners for a New Economy (P4NE). Established in 2015, P4NE is a group of foundations that had been funding environmental projects without seeing any tangible benefits. Oak, MAVA, Marisla and KR Foundations set up a “high-risk, high-impact donor collaborative focusing on the economic system as the root cause.” The benefit of this partnership is an increasingly creative way of structuring economic systems in order to generate positive social and environmental outcomes. Jo Swinson, former leader of the UK’s Liberal Democrats. She explains how P4NE is actively tried to make structural changes that will have long-term resonance. “In order to create change within a system, you need lots of different people trying to make different changes. But the part that we are focused on is trying to see where the edges and the frontiers are and how we can expand those. So taking the emerging ideas and nurturing them… giving them the chance to grow and to develop so that they can move towards the mainstream.”

As a race, tackling climate change seems like one that we are destined to lose. Working alone has, to be fair, largely contributed to the mess the environment now finds itself. It is only through collaborative action, both through innovation and investment, that true solutions can be found.